Historical Context

The Hussite revolution, which in years 1419 – 1434/36 ran through Bohemia and partially also other Bohemian Crown Lands, was a result of a deep economic and social crisis. The death of an influential preacher and scholar Jan Hus, who was burnt to death in 1415 in Constance upon the initiative of the Catholic Church, was a detonator for the whole revolution.

His legacy on the reformation of the church, or more precisely the whole feudal society, was an inspiration for a wide part of Czech society ranging from the poor and common people from the country to townspeople and nobility. After the death of Wenceslaus IV in 1419 their representatives refused to acknowledge the successorship of his unpopular brother Sigismund.

He was determined to get the crown by force. In order to defend themselves against him and other enemies (pope, Catholic Church and part of the domestic nobility) the Hussites, more precisely Utraquists, how the followers of Hus’s ideas and communion under both kinds called themselves, gathered substantial military force and unusual but effective tactics of fighting. They managed to fight off all four crusades 1420, 1421/22, 1427, 1431.

Although the last one of them was, regarding the strength of the armies and quantity of means put in, the biggest one, it finished with unequivocal, famous and problem-free victory of the Hussites in the Battle of Domažlice.

Preceding Events

After the victory near Tachov 1427 the Hussites’ military force was at their peak and their enemies for a long time lost courage to fight. Unlike in other years there were in that time not such strong troubles between the individual streams and representatives of the movement. The stabilized situation enabled the Hussites to make successful Hussite raids, campaigns in order to get the spoils and to make propaganda to neighbouring lands.

Proportionally to the growing daring there were, and not only in the German areas, more and more voices calling for stronger action against Bohemian heretics. For this purpose, near the Bavarian city of Weiden near the Bohemian borders a large (for that time large) army started to assemble mainly from German, but also Hungarian and Italian troops. The pope appointed his legate (envoy) cardinal Guiliano Cesarini to organise this army.

Sigismund of Luxemburg, the king of the Holy Roman Empire, the king of Hungary and formally also the Czech king, did support the campaign, but he managed to wriggle out and he once again appointed the Brandenburg margrave Frederick, the unsuccessful commander of the previous crusade, as the commander. The crusaders, however, experienced from the preceding failures, planned to defeat the Hussites with their own tactics with help of 9,000 battle wagons.

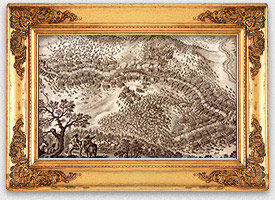

In this way armed army numbering over 100,000 men crossed on 1st August the Czech borders and was moving towards the Hussite town of Tachov. They, however, did not succeed in capturing it in several following days, by which the course of the events started to resemble the unsuccessful crusade four years earlier. They moved, out of caution, to strategically more advantageous town of Domažlice, which they meant to get as their supporting point.

The Hussites were well informed about the preparations and movement of the crusaders and gathered an army numbering about 40,000 men in the surroundings of Beroun in a very short time, by the way this was also the largest one in the history of these wars. The speed and willingness with which this all happened proves the concord of the Hussite streams of that time. Even though the number of the Hussite army did not reach even the half of the army of the enemy, but they exceeded them with their organized character, battle moral and unity of the command. It was an excellent strategist Prokop the Great who was appointed into its lead. In order to prevent the crusaders from capturing Domažlice, the Hussites on the 12th August set out.

Course of the Battle of Domažlice

The speed itself with which Prokop the Great’s army came to Domažlice (approximately 80 km in two days!) surprised and scared the Crusaders. The chaos brought among them was also caused by confusing movements accompanied by a bad coordination of such a huge number of troops. In the space between Domažlice and the Castle of Rýzmberk they quickly built a barricade of wagons, however, most of the troops did not have enough time to take up fighting positions.

The further course of the battle is rather mysterious. It is spoken about a perfect example of a “psychological effect” in the war history. The advanced Crusaders’ troops who on the day of the battle on 14th August in the morning are said to have heard the rumble unexpectedly early coming Hussite wagons accompanied by Hussites singing the chorale “Ktož jsú boží bojovníci” (Ye Who Are Warriors of God) started to withdraw quickly.

This tactical move then totally weakened the battle morale of the confused and scared soldiers of the main part of the Crusade army, who started to leave their positions on a mass scale and ran away towards the Bavarian borders. The commanders failed to stop them from the escape and in the end they had no other choice but to follow them. In this way, it is said, even Cesarini himself saved his life disguised as a common soldier.

His cardinal’s hat left on the battle field entered the history as a symbol of the Hussites’ triumph over the Crusaders and Catholic Church and for a long time afterwards it was displayed in Prague in front of the Church of Mother of God before Týn. Up to 2,000 fully equipped battle wagons, military material and various precious artefacts fell to the Hussites’ hands

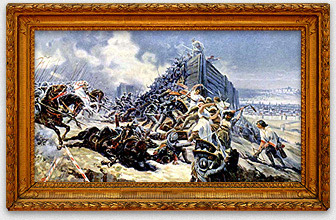

There were only foot troops with their barricade of wagons fighting back the Bohemians by which they indirectly helped to prevent a larger carnage which for sure would follow after the immediate catching the running troops. The Hussites succeeded in overcoming this obstacle first after several hours of fighting and then there was not enough time and energy to chase the enemy.

Result

The result was a crushing victory of the Hussites, who without any considerable losses dealt with the last foreign intervention of the revolutionary part of the Hussite wars. They once again assured Christian Europe of their military invincibility. With exaggeration we can say that the Crusaders trying to stop the Hussites from further plundering of the neighbouring lands brought them rich booty straight to Bohemia.

Similarly to the case of the preceding Crusade this campaign was also without any delays and casualties. These can be, on the side of the Crusaders, estimated in hundreds, especially among the foot soldiers of the barricade of wagons (among others over 200 Italians). The Battle of Domažlice actually copied when it comes to its course the events linked with the Battle of Tachov in 1427.

Historical Importance

The Hussites’ victory at Domažlice finally convinced their enemies of the hopelessness of the solving the situation in Bohemia by power and it opened a way for negotiations. It was the same cardinal Cesarini who then contributed to the negotiation of the representatives of the Council of Basel with the Hussite delegation in 1433 led by Prokop the Great.

The mutual opening to a compromise agreement helped together with the gradual discord inside the Hussite movement to bring the conflict to its end (Lipany 1434, the acceptance of the Compactata 1436) and acknowledging Sigismund of Luxemburg as Bohemian king.

Author: RNDr. et PhDr. Aleš Nováček, Ph.D.