Historical Context

A rather fast development of society, economy and culture in Western and Central Europe in the time of the High Middle Age, i.e. from the 11th to the mid-14th century changed to a crisis which started in the mid-14 century. The pillars which till that point built a stable basis for the middle-age feudal society started to tremble. There were plague epidemics (the biggest one was in the mid-14th century) which martyred the people and were bringing numerous deaths to them on regular basis. This significantly interfered with the economic system, the long-distance trade was collapsing and the position of the serfs was getting worse.

Common people missed existential securities. The spiritual role of the Catholic Church was stepping back proportionally related to the increase of its political and economic power. In addition, its authority was in years 1378 – 1417 seriously undermined by the papal schism, a situation in which two or even three popes tried to get to the lead. This situation brought several attempts to reform the church, or more precisely the whole feudal society.

The most successful one became the Bohemian Hussite movement, which arose from the thoughts of a reformatory theologist and preacher Jan Hus. One century later, already at the door of the Modern Age, even the German reformation drew inspiration from him. The Hussite movement spread quickly within the inner Bohemia, less then within the other areas of the Bohemian Crown Lands. It was especially the Bohemian townsmen, knights and common country people and the poor who belonged to its followers.

Everything culminated in the form of revolutionary events during the years 1419 – 1434/36. In order to defend themselves against the outer (Catholic Church, pope, king and later emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg and other organized crusades) and also the inner enemies (Catholic nobility, Catholic church and their followers) the Hussites created substantial feared military power and well thought-out tactics of fighting.

The enemies were not able to defeat them by power; all of their four crusades were doomed to failure: 1420, 1421 – 1422, 1427, 1431. Only the diplomatic negotiations (in Basel 1433) and gradual inner disagreements among the Hussites helped to bring the conflict to its end (Lipany 1434, acknowledgement of Compactata 1436 by Sigismund of Luxemburg).

Preceding Events

After Hus’s burning in Constance (1415) the discontent and opposition within Bohemian society to the Catholic Church, or other feudal authorities grew significantly. The bloody New-Town-Hall Prague Defenestration on 30th July 1419 is usually considered to be the beginning of the revolution. Short after that king Wenceslaus IV died and the country fell into a chaos in which it is easy for the Hussites to push through their goals and to gain control over numerous seats and areas.

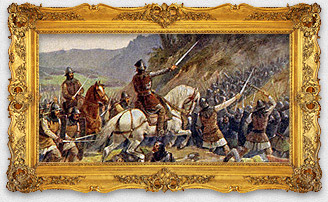

The first phase of the revolution (i.e. 1419 – 1429) started. This phase was characterised by its spontaneity and formation of the military force of the Hussites in order to defend the movement which was coming into existence. With the aim to get rid of the heresy and to gain the reign over the Bohemian Lands after his brother Roman king Sigismund of Luxemburg organized a crusade in spring of 1420. He invaded Bohemia in May and with its total number of the soldiers this crusade represented the biggest foreign army which till that time entered the territory of the Czech state.

The estimation of number of its soldiers ranges from the conservative 30,000 to hardly realistic 100,000 men, the most often given number is 50,000 – 60,000 men (this number was even exceeded in the 4th crusade in 1431 which is said to amount to about 100,000 men). Against them the Hussites were hardly able to get together 30,000 of their armed men, most of them originally peasants and craftsmen without any fighting experience.

Very often it was also women and children fighting among the warriors, but even they did not lack the determination to rather lose their lives for their faith and belief. The crusaders’ attack was aimed at Prague, the capital of the kingdom and the centre of the Hussite movement, where its further existence was to be decided. In order to help their Prague brothers the Hussites from Southern (the Taborits), North-Western (Union of Žatec and Louny) and Eastern (the Orebits) Bohemia came to Prague.

During the time of the Battle of Vítkov there were only 12,000 – 30,000 mainly badly armed and trained warriors who could defend well-fortified and well-stocked Prague. The situation was, however, even worsened by the fact that two out of three strategic strongpoints which were in immediate proximity to Prague – the fortress of Vyšehrad and Prague Castle – were in hands of Sigismund’s followers. The third strategic point was the fortified hill Vítkov. This and the neighbouring Spitalfield (currently Prague district Karlín) were the places for a most suitable way to conquer Prague.

That is why the Hussite leaders appointed the Taborits with Jan Žižka and his defence in the lead. Because of the steep slopes the attack on Vítkov was possible only from the East. Žižka had this part thoroughly fortified with a palisade and two wooden log cabins. In early July most of the crusader army with Sigismund in the lead were already waiting in front of Prague.

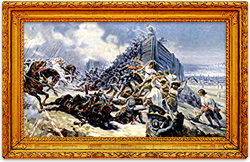

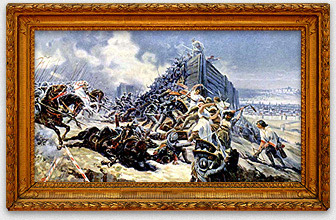

Course of the Battle of Vítkov

Because of the financial problems it was impossible for Sigismund to prolong the crusade; therefore he decided to attack immediately instead of a lengthy siege of Prague. The attack was planned from three sides. The main squad was supposed to cross the Spital Field and Vítkov and it was supposed to be completed by forays from Vyšehrad and across Charles Bridge. The only thing which was in the way of this plan was the fortified hill Vítkov with Žižka and his people on it (the sources speak of only 26 men and 3 women!)

On 14th July the main part of the crusader army forded to the right bank of the Vltava River and they started to pretend to be attacking on the area of Spital Field. Other troops of approximately 7,000 – 8,000 men-at-arms mainly from Meissen and Austria led by Meissen margrave Frederick IV the Belligerent and Pippo Spano of Ozora attacked Žižka’s positions on Vítkov from the East.

Because of the narrow access path and tenacity of the defenders they were not able to use their superior numbers. However, the situation was becoming more and more critical and some invaders did succeed and got into the log cabin. At the right moment the reinforcements of the bowmen and fighters with flails sent from Prague entered the fights. During the counter strike whose effect was made even stronger by Hussites’ war cry the Crusaders were driven away. Many of them died when they fell from Vítkov hill. The discouraged Crusaders were not able to repeat their attack.

It was only one hour of fighting and the heroism of a few Hussite warriors which decided the fate of the First Crusade and may be the fate of the whole Hussite movement. The clash itself claimed roughly 100 – 300 casualties on the side of the Crusaders, but we lack any estimation of the casualties on the side of the defenders. Later Sigismund’s armies had to face other problems with paying out their wages and the fire in their camp which did not help the frustration of the soldiers. In this situation there was no other solution for Sigismund but to give up the idea of capturing Prague and to dissolve the First Crusade against the Hussites. On 28th July in St. Vitus Cathedral (Prague Castle was controlled by his troops) Sigismund was crowned as the Bohemian king, but later he also withdrew to the safety of Kutná Hora (Kuttenberg).

This was the end of the imminent danger to Prague and its allies could go back home. The situation in the city, however, still remained complicated. The danger was in both strategic fortresses, Vyšehrad and Prague Castle, which were still under the control of Sigismund’s followers. People of Prague then decided to surround Vyšehrad whose army of 4,000 men was led by Moravian nobleman Jan Všembera of Boskovice.

Once again in October all Hussites from whole Bohemia came to help the people in Prague. Vyšehrad was facing quick starvation. Its commander was therefore forced to make an agreement with the besiegers in which he was promised to get the possibility to leave and to hand over the fortress to Hussites if he is not freed by Sigismund’s armies by 1st November by 9 o’clock (some sources speak about 8 o’clock) in the morning. Sigismund’s armies were again getting closer to Prague in order to fight a battle which was supposed to break through the siege of Vyšehrad and with the help of its garrison and the raid from Prague Castle to lead to capturing the whole city.

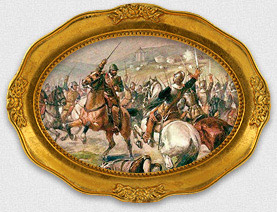

Course of the Battle of Vyšehrad

The states of both belligerents were much more equal this time. Also in this time it was Sigismund’s army which was stronger and put together from Hungarian and German mercenaries and from Moravian and Bohemian followers of the Roman king, altogether 16,000– 20,000 soldiers. Against them on the field in front of Vyšehrad there were 15,000 Hussite warriors led by Hynek Krušina of Lichtenburg. Their defensive posture was in all sides even stronger thanks to the belts of fosses, embankments and several wooden cabins. The order to attack was given by Sigismund on 1st November in the afternoon.

The question is if he was acquainted with the agreement between the garrison of Vyšehrad and the Hussites. The Hussites, anyway, did obey the agreement and did not fight as it was already after 9 o’clock in the morning. The attack against the Hussites was led from the South. While Hungarians and Germans attacked frontally, Moravians outflanked from the left even though it was difficult because of the rough terrain. Their effort brought partial success, they managed to break the Hussites’ defensive line and force them to partially withdraw. Hynek Krušina reacted to this critical situation with calling up the reserves and together with them he stroke back in which Sigismund’s soldiers were forced to withdraw and many of them, mainly Moravians, were killed when they were moving back.

Result

The Hussites’ success is also proved by the inequality in casualties. The estimations speak about 30 killed on the side of the Hussites, on the side of their enemies the number of casualties could be around 500. Jan Všembera handed over Vyšehrad to people of Prague and his garrison was given the chance to leave freely. Also the second Sigismund’s attempt to capture the capital of the Bohemian Kingdom failed.

Historical Importance

The years 1419 – 1420 present the first phase in the Hussite revolution, it was the time filled with idealism, energy and determination, but at the same time it was a period when the whole movement was young and vulnerable. The Hussites’ victories in the Battles of Vítkov and Vyšehrad prevented the foreign and domestic reaction from destroying the movement and enabled its full development .

Thanks to them the Hussite warriors and their commanders (especially Jan Žižka) won respect even abroad. However, not even these victories were able to discourage the enemies from other attempts to put the military situation in Bohemia to the original state and to bring the local people back to the Catholic Church.

Author: RNDr. et PhDr. Aleš Nováček, Ph.D.