Historical Context

The Battle of Zborov is one of the smallest clashes which was included in the Project Bellum.cz, regarding both the number of the soldiers who participated in it, and the size of the battle field or the impact on further course of the war. The results of this quite small battle, which took place within the First World War in Western Ukraine near a Ukrainian town Tarnopol (to the north of Lviv), were, however, crucial for the further shaping of the Czechoslovak troops in Russia, and especially for the successful development, support and acknowledgment of the thoughts of the Czechoslovakian foreign resistance.

From the point of view of the course of the so called Great War this was just a small episode. The attack of the Czechoslovak Riflemen Brigade near Zborov, no matter how successful, it was a part of the Russian so called Kerensky’s Offensive, which ended in a complete failure followed by a withdrawal and leaving the positions.

By mid-1917 all the participating parties had already got to know the frightfulness of the trench warfare battles, tens of thousands of the dead in a single day within a short passage of the frontline and the offensives in which the only success often was only a few gained kilometres of a destroyed area. This immobility of the frontline was typical especially for the so called Western Frontline, a line stretching between the Belgic coast and Switzerland.

The reason why the trench warfare when the defence dominated over the attacking forces arose was especially the mass using of the 19th century invention – machine gun and also extensive using of the cavalry which managed to kill an attacking soldier on the plain much better than the one hidden in a deep trench. Neither the invention of the tanks nor the extension of the combat aviation, which gained its fame during the First World War, which paradoxically led to the boom of the aviation in the after-war peaceful time, managed to disrupt the static defensive line.

Preceding Events

The mid-1917 did not bring any significant changes regarding the European battlefields; the USA entered the war already in the spring, the tsarist regime in Russia had fallen by that time as well. The latter, however, had a huge impact on the further events resulting in the Battle of Zborov.

Until that time unstable Russian army became even less reliable and its fighting force shrank dramatically. This situation was even supported by the growing agitation of the Bolsheviks both among the soldiers and in the base. The chaos in the base was also growing and the so called interim government of the Russian socialists tried to stop it by a great success on the frontline. The new commander-in-chief until that time a relatively successful general A. A. Brusilov tried to launch an offensive which is named after the Minster of War and later also the Prime Minister A. F. Kerensky.

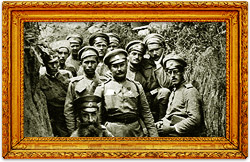

Brusilov tried to use the still fit-to-fight troops which were not be affected by the agitation and disintegration, and he thought that these troops would set a good example and be a uniting element. When looking for such troops the general also found the newly established 1st Czechoslovak Riflemen Brigade, which was solely formed of volunteers. The offensive was planned with 3 Russian armies, in total about 30 infantry divisions, 5 cavalries and more than 1,000 canons. Among them, the Czechoslovak brigade was only a drop in the ocean. Yet while the legionaries being excited and enthusiastic (which from the today’s point of view would hardly be seen as a mere patriotism) were eagerly getting ready for the first joint attack of so many Czechoslovaks against the armies of “their” Austria-Hungary, some of the Russian troops had to be in the evening before the outbreak of the offensive disarmed as they refused to obey.

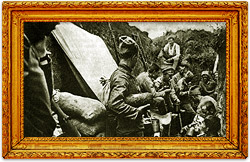

On the other hand, the 1st Czechoslovak Riflemen Brigade did not get the basic parts of the fighting equipment, actually they hardy had any machine guns, and also the other equipment was not sufficient. Even though it was hot July, quite a few soldiers had to wear the winter clothing like fur coats, fur hats and felt shoes as their uniforms. The troop was not coordinated at all, as most of its members were earlier dispersed along the whole frontline among the Russian troops were they served as scouts in the first line.

The Czechoslovak brigade consisting of 3,530 men was originally meant to fight within the main attack of the whole offensive, which means on a very strategic position. The Russian commander of the brigade (the high command had to be Russian only) Vyacheslav Trojanov was because of the lack of sufficient training and equipment against this idea, and that is why the whole brigade assigned to the 11th army whose task was to lead a supporting attack in the southern area of the planned offensive. The brigade was meant to be a shied in the middle of the two Russians divisions, the Forth Finnish Riflemen and the Sixth Finnish Riflemen divisions (the divisions were not formed by Finns but by Russians but the name was without a doubt after the place where the garrison was active before the war). The beginning of the attack was supposed to be secured by both divisions, whereas the Czechoslovak brigade was supposed to attack first after their penetration into the centre of the Austrian defence.

Behind the no man’s land there were the trenches of the Austro-Hungarian army, which was very well informed about the coming offensive and therefore ready. Its defence consisted of three defensive lines, and each of them was formed by a whole range of trenches. The defenders were members the 2nd army, more precisely the 9th corps, whereas against the Czechoslovak brigade there was mainly the 19th division. It was quite ironic that more than a half of this division consisted of Czech soldiers. Nobody on either side knew anything about the fact that this would be a fight where men of one nation would fight against each other until the clash broke out.

Course of the Battle of Zborov

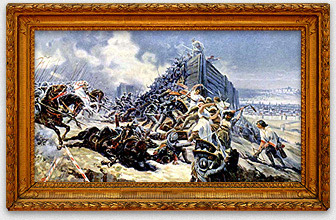

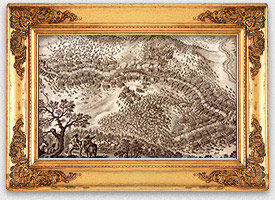

Kerensky’s offensive started on 1st July 1917, one day later it was the time of the southern sector. At 5.15 a.m. the artillery preparations started, these were followed after eight o’clock by the attacks of both Finnish divisions. 45 minutes later, at 9.07 a.m., also the first parts of the Czechoslovak brigade launched their attacks. At first in the northern section, ten minutes later in the central one and finally, in spite of the opposition of the Russian commander, the southern section took the initiative at 9.30 a.m. At that time the northern and central parts of the trenches of the first Austrian defensive line were seized. At 10.00 a.m. the Czechoslovak brigade controlled the whole first defensive zone.

None of the Finnish divisions, however, succeeded in getting through the first defensive zone, which made the whole situation rather complicated, because both wings of the penetrated legionaries were exposed to attacks, especially the right wing got stuck for some time. In its close proximity there was a well-fortified spot height 394 Mohyla, which was supposed to be, according to the plan, in hands of the Russian division, this, however, was still not successful. Yet the other parts of the Czechoslovak brigade continued in their successful advancement and at 10.45 a.m. they also controlled the second Austrian frontline.

The success of the Czechoslovak brigade, which in original plans, was only supposed to have a secondary role, attracted the attention of the commander of the corps and the reserve 82nd division was heading at that area. Around 11 o’clock they managed to get control over the fortified hill, spot height 392, which divided the Austro-Hungarian position into two parts, but Mohyla was still fighting back. Meanwhile, around 12 o’clock they managed to defeat on several places also the last third reserve defensive line. After that the situation in these segments of the frontline got stable, because the brigade together with the reserve 82nd division and the 4th Finnish division concentrated on capture of the strategic hill Mohyla. This was defeated at around 2 o’clock p.m.

Result

The military success of the Czechoslovak brigade was so resounding that the whole Russian leadership was totally surprised. What was a failure for much larger troops, was a success for a troop which was, because of its equipment and training, considered second-rate. At the beginning the advancement of the brigade was suspicious, for example one Russian lookout being in a balloon above the frontline thought that the Czech soldiers were deserting, as he was not able to find any other explanation for such a fast advancement.

There are a lot of factors behind the success; the most important one of them is certainly the moral of the members of the Czechoslovak brigade and also the way of their fighting. The soldiers were attacking as they were used to when they were scouts, in small groups of only several men, which helped them to be able to hide from mortal machine gun shooting. Actually it was the fact that they were put into one troop without any further coordination, which was not bound by a doctrine and also the initiative of the lower officers who were able to react promptly to any problem.

The Czechoslovak Riflemen Brigade lost on 2nd July 167 soldiers who died and 1,000 who were injured. At this cost they, however, managed to get through all three enemy zones and moreover to capture more than 4,000 men, which was more than the number of soldiers of the whole brigade. There were several hundreds of dead Austro-Hungarian soldiers within the area. Unfortunately, this enormous success was not taken advantage of in the end, the Russian army did not have in this side area other reserves which would be able to use the penetrated frontline and continue further to the west.

Historical Importance

On the whole, the Kerensky’s Offensive soon ended in failure, because there were not enough determined troops which would be able to develop this launched attack and therefore after several days it was the Austro-Hungarian and German armies which started their counteroffensive. Even though it was a military failure, the Battle of Zborov brought a decisive positive turn. Not for the Russian frontline, which definitely broke down not long after that, but for the Czechoslovak foreign policy. Firstly, the Russian government and military leadership said amen to extension of the Czechoslovak troops which later turned into powerful military forces in Russia.The battle had a great political importance, because after it was over the views of the Czechoslovak foreign resistance were accepted by the agreement allies much better and some further possibilities for later support of the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic, the Czechoslovak foreign resistance started to be a relevant political force, as there was a successful and quickly growing army behind it.

The Czechoslovak legions was gradually getting into an unenviable situation after the Bolshevik revolution (which broke out in the autumn 1917) and after the peace conclusion between Russia and the central powers. Yet, they were able to gain a lot even from this situation and for several months they managed to keep control over vast areas in Siberia. Their withdrawal into a newly established homeland was a must, even though the legionaries often got back first in 1920.

But it was these troops that helped a lot (and not only with the Battle of Zborov) and indirectly supported the establishment of Czechoslovakia. Thanks to that the Battle of Zborov became a legend and the soldiers who took part in it glorified heroes. This symbol was then being removed during the Nazi and later communist regime, and therefore today it is not so known as it was in the times of the First Republic. Although the excited nationalism and excitement of the men plunging into mortal fights can only hardly be understood today, the Battle of Zborov is an integral and important part of the Czech history. That is why it does deserve, after it was deprived of the legendary image, nearly miraculous actions and one-sided glorifying, to paid close attention.

A number of important personalities wearing the uniform of the Czechoslovak brigade took part in the Battle of Zborov. These being for example Jan Syrový, the later important general and during the Munich Crisis for some time the Prime Minister and the Minister of National Defence, who was because of the loss of his right eye during the battle and for wearing a black eye patch over it called “Žižka of Zborov”. Further we can name for example the writer Rudolf Medek or a controversial personality Rudolf Gajda, who became a general in 1918, but for his political influence he was in Czechoslovakia in the 1920s unjustly accused of a coup attempt, which made him unite with the Czech fascists.

Author: Mgr. et Mgr. Jan Rája