Historical Context

The Battle of Königgrätz, also called as the Battle of Chlum or Battle of Sadová/Sadowa, was the most important and crucial clash of the Austro-Prussian War in the year 1866. It took place on the area of the then Habsburg Monarchy not far from two important fortresses – Josefov and Hradec Králové (Königgrätz).

Since the time of the Seven Years’ War and also the Battle of Kolín it had been several decades, but nothing had changed in the sense that there were two strong monarchies next to each other within the area of Central Europe, which very often got into disputes because of their effort to be dominant in the region. Since the Seven Years’ War, however, a lot had changed when speaking about the inner organization of the states, their borders, and especially the biggest changes were in society. And those changes were really significant. The nobility was losing its privileged position, in both countries the industrial revolution was in progress, gradually both the serfdom and servitude were abolished and a big novelty of the 19th century was on the rise – the nationalism.

After some calming down of the relations between both countries during the Napoleonic Wars, which forced the original enemies to alliance, there were decades of a relative peace until the revolutionary year 1848. It turned out that Austria would not on the lead of the attempts to unite Germany, but Prussia did have such claims. The accession of Otto von Bismarck as the first minister of Prussia the situation between both countries inflamed.

Preceding Events

Bismarck knew that it was important for Prussia to force Austria out from the events in the German Confederation and that the best way how to do it would be with military forces. The pretext for that was the dispute of the future of Schleswig and Holstein. At first the war was favoured neither in Vienna nor in Berlin nor in any other German land, but Bismarck, within six month, succeeded in pushing through the war not only at home but he was also able, with help of ingenious manoeuvres, to impose it to his enemies. The war was declared against Prussia by many states of the German Confederation, but their military help to Austria was negligible. It was only Saxony that send its army to help Austria, after all, its troops would have got into Prussian capture if they had not.

Prussia, however, was not the only country which declared war on Austria. Since newly united Italy intended to annex Veneto to its state, which was still under control of the Austrian Monarchy. That is why the union of Italy and Prussia against Austria was a logical movement.

Therefore, Austrian army had to divide into two parts. The first, larger one concentrated in the border area with Prussia, which means mainly in the Bohemian Lands. The southern army then was getting ready to fight in the endangered Veneto. The war broke out in mid-June 1866. The secondary battle field in Italy witnessed the Battle of Custoza, where the Austrian forces were outnumbered and still managed to defeat the Italian army. The war was, however, to be decided in the North.

The commander of the Austrian army, field armourer Ludwik von Benedek concentrated at first the main forces in the surrounding of the fortress city of Olomouc, and after the invasion of the Prussian army into Bohemia he moved the army to Eastern Bohemia. The Prussians were moving ahead in three flows so that they would reunite on the spot of the next battle field, which was a plan of the experienced chief of the Prussian general staff, Helmut von Moltke. The Prussians crossed the borders of the Monarchy near Rumburk (the Elbe Army), Liberec (the First Army) and Trutnov and Náchod (the Second Army). During their march these armies fought several times successfully against the Austrian army, which forced Benedek to withdraw to the city of Königgratz, concentrate the whole army there, awaiting the decisive battle, which broke out on 3rd July 1866.

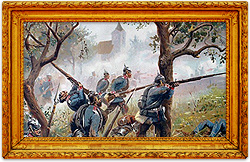

Course of the Battle of Königgratz

Number of the participation soldiers was rather even: the Prussian army accounted about 220,000 men, the united Austrian and Saxon army about 215,000. The Austrian forces were positioned into a rough semi-circular defensive line, its rear was backed up by the river Elbe and the Fortress of Königgratz. The attack of the Austrian positions started before 7:30 in the morning and was gradually growing until approximately 10:00 in the morning, when the forces of the Elbe and First Armies were already involved in the battle.

These troops were coming from the West and North-West and were attacking in the direction of Nechanice, Popovice and mainly the area of Sadové. In the morning the situation was even, the defenders rather managed to fend off most of the attacks and they even counterattacked. It was the Austrian artillery that was of great help, as thanks to them the attack at Sadová was stopped.

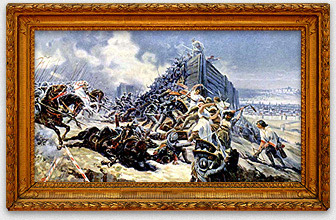

In the north-western defensive line there was something going on that the commander Benedek had no idea of. One of the Prussian infantry divisions got into the Svíb Forest, which was behind the first defensive line. It still was no real disaster, but what was more important for the course of the battle was the fact that in order to push them out of the forest, several Austrian divisions joined in, which were supposed to wait for the coming of the Second Prussian Army marching from the North. The area which was supposed to be defended by these troops (in particular those were the corps II and IV) became the decisive spot of the battle field. Several hours lasting fight for the Svíb Forest enabled the Prussian army to redeploy without being watched to the rear of the Austrian army, all the way to the Village of Chlum (which they captured at 2.15 in the afternoon), which was near the position of Benedek and also the large Austrian reserves.

When Benedek found out from his subordinate that a fire on him was opened from Chlum, he did not want to believe it and he himself went to check the situation, but the Prussian bullets forced him to withdraw back. The situation in that moment was for the Austrian party really critical because the enemy at the rear of their troops was a mortal danger. An immediate decision was made – to attack the Village of Chlum located on the hill, which was at that moment a significant barrier for the Austrian forces.

The first attack of the Austrian troop was surprisingly successful, but thanks to the lack of other forces which would join and support the only brigade, the troop was pushed back. When they succeeded in gathering a storm troop including the whole corps VI and then also the corps I, the whole hill near Chlum was full of other Prussian troops.

Result

The following attacks of the Austrian infantry were a disaster and left about 10,000 dead, injured and captured. The only remaining thing was to safe the defeated army. Roughly since 4.30 in the afternoon the whole Austrian army was withdrawing towards the city of Königgratz. The cavalry and artillery very successfully covered the withdrawal of the infantry. This, however, did not change the fact that the battle was lost. In the Battle of Königgratz on the side of the Austrian army nearly 6,000 men died, 8,500 were injured and almost 22,000 captured. They also lost about 188 canons, which was a large part of the artillery. The losses on the Prussian side were much lower, almost 2,000 dead and 7,000 injured.

The arms are very often mentioned as the reason of the Austrian army’s defeat. It is definite that the Prussian “breech-loaders” (rifles loaded from behind and not form the front – the old way of the loading) were more modern, but still until today generally accepted information on their quality are probably exaggerated. The speed of the loading, according to some authors it was four times faster compared to the Austrian “muzzle-loader”, was probably not so much higher.

Moreover, the Prussian Dreyse needle gun had a number of maladies and were not very reliable. But even if the more modern Prussian rifles had been better, then in other important arms, artillery, the situation was reversed. The Austrian forces had at their disposal many more modern canons with internal threads, which were much more precise and had a longer firing range. The arms of both armies probably were not what would decide the battle, even though they are given too much credit for that.

During the following days the Austrian forces withdrew via Olomouc towards the South, and although they were forced to leave Moravia, they managed to unite with the army which won in the Italian battle field. On 26th July, however, armistrice was concluded in Mikulov (German: Nikolsburg), which was followed by the Peace of Prague signed on 23rd August 1866. Such quick peace was concluded after Otto von Bismarck’s urge who on the contrary from the corps of generals and also the Prussian monarch anticipated that Austria could be for the future a good ally, especially when France led by Napoleon III was getting ready for the war which Bismarck wanted to postpone at that time.

Historical Importance

The results of the Battle of Königgratz / Hradec Králové and the whole campaign were already definite, but what did they mean for the Austrian Monarchy and then also for the Bohemian Lands? At first, it was the loss of the Austrian position of the great power which was not meant to return to the monarchy any more. Austria had to surrender Veneto to Italy, to give up the rights to Schleswig-Holstein in favour of Prussia and especially to agree with dissolving the German Confederation and creating the North-German Confederation under the lead of Prussia.

Thanks to this Austria definitely lost the chance to influence the events in disintegrated Germany where it had kept a considerable influence for several centuries. This actually led to the union of Germany in Prussian hands and to creating even stronger hegemonic leader of Central Europe. The peace which was signed in Prague by Austria and Prussia also meant the future rapprochement of both countries which was something that the Prussian representatives counted with. The defeat in the Battle of Königgratz sent Austria to a strong ally which drew it to the First World War and then did not let go from its embrace even in the mortal agony of the end of the war. This sealed Austrian-Hungarian fate.

Apart from the clearly reduced influence of Austria the defeat brought a dangerous strengthening of the nationalism inside the country and further weakening of the powers of the monarch Franz Joseph I regarding the internal matters. It also helped to finish what the political scene in Hungary had been trying to reach for a long time: dualism and establishment of Austria-Hungary in the year 1867, which meant a great autonomy for the Hungarian Lands. Austrian-Hungarian settlement contributed, at the beginning, to internal stabilization of the country, but on the other hand it was a thorn in the side of many of the Slavonic nations which were part of the Monarchy.

The Battle of Königgratz and the defeat of the Austrian armies meant a lot also for the Bohemian Lands. It was not only occupation by the Prussian troops, but especially the disappointment by the further course. After declaration of the dualism the Bohemian political scene was not able to properly react and in the following decades it fought rather inside against itself than together for the “new” national issue.

The following disputes with the representatives of the German minority within the area of the Bohemian lands, failures of the attempts to enforce the “Austrian-Bohemian settlement” and many other causes led to escalation of the situation and strengthening the national feelings. This, however, meant in the end that many inhabitants of the Czech nation turned bitter regarding the future of Austria-Hungary and it actually led to refusing to obey the Emperor by some important personalities of the Bohemian political scene during the First World War.

Author: Mgr. et Mgr. Jan Rája